AN INDUSTRY IN THE MAKING

HISTORY: GERMAN FILM ABROAD BEFORE AND AFTER THE SECOND WORLD WAR

In 1954, the Export-Union des Deutschen Films (today: German Films) began its work to support the export of West German films by providing advice, promotion and marketing measures. It was headed by Günter Schwarz, an experienced film export official who had previously served the Nazi regime for years in the Film Chamber of the Reich (see GFQ 1/2024) and who was now supposed to help the blossoming German film internationally. But why was it necessary to establish such an organisation in 1954?

International Press Articles 1950 © German Films

A statistic handed down by Thomas H. Guback provides an example of where West German film stood internationally in the 1950s: In Canada and the USA, no fewer than 74 German films were released in cinemas in 1956, almost twice as many as French films. However, the combined revenue from their release totalled just 282,000 dollars (equivalent to around DM 1.2 million) – a tenth of what the French films grossed. The “Filmstatistische Taschenbuch“ puts the total West German export revenue for 1956 at DM 14 million. In other words: While domestic films set records at home with a turnover of DM 154 million (1956 in West Germany), international interest in them was marginal.

There are a number of reasons for this clear concentration of the West German film industry on the domestic market, which it largely dominated in the 1950s, and the resulting weakness in exports after the end of World War II. At least before the war, German film was in a completely different position internationally.

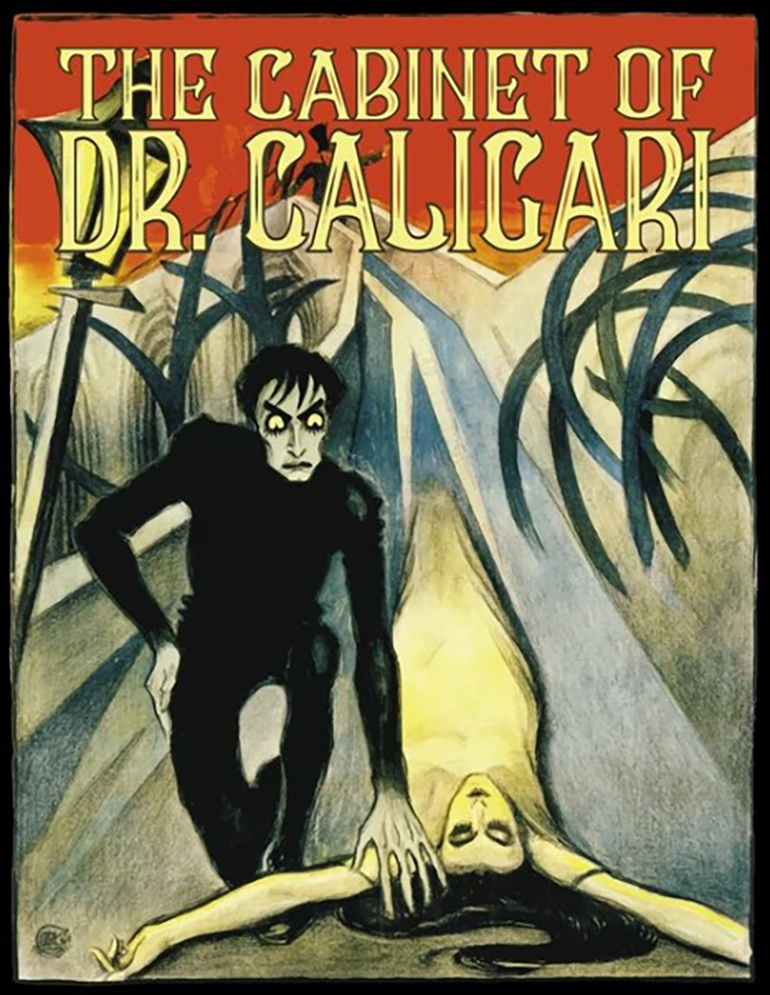

Between 1919 and 1933, German film enjoyed its most productive and internationally successful phase. There were many reasons for this: For example, the young German film industry was in a much stronger position than most other countries after World War I. In addition, a quota law first curbed film imports, then a compensation system was introduced that provided for a new German production for every import. Then there was inflation, which made German films extremely cheap and also reduced the risk of venturing into cinematic experiments. All this led to an enormous output – up to 500 films were produced annually, flooding the international market at favourable prices. A few exceptional films further fuelled the interest and reputation of German film. Robert Wiene’s THE CABINET OF DR. CALIGARI, for example, was a great success throughout Europe in 1920, while Ernst Lubitsch’s PASSION was also shown for weeks in the USA in the same year.

The Cabinet of Dr Caligari Poster © Transitfilm

Lubitsch’s immense success triggered a veritable export boom of German films in the USA for a short time. In her book “Foreign Films in America“, Kerry Segrave recounts in detail the almost hysterical reactions to the glut of inexpensive German productions. Once, when 46 German films were announced in one release week, there were veritable protest marches in Los Angeles on Miller’s Theatre, which had planned a matinée of THE CABINET OF DR. CALIGARI in April 1921.

While rotten eggs were being thrown at the cinema there, a law was being considered in Venice, California, which would force cinema owners to buy a licence costing 50 dollars a day if they played German or Austrian films. High tariffs for German films were also being discussed in order to protect American films from the superiority of German films. The New York Times took a more relaxed view and argued on 19 April 1921: “It is also true that the German feature films lately shown here are better than anything that ever came out of Los Angeles“. A day later, it added: “The real German menace in the moving picture field is the menace of superior intelligence“.

At the end of June 1921, Variety ran the headline “German-made films now found to be heavy drug on market“, but after a few months, the excitement died down and interest in German film increased. After all, films such as CALIGARI, PASSION or Fritz Lang’s METROPOLIS were notable exceptions in a German mass industry of that time – the majority of productions that left Germany’s film factories at the time were clearly of inferior quality. Nevertheless, in the years between 1923 and 1935, the proceeds from German film exports accounted for between 20% and 50% of total production income.

Moreover, by the end of the 1920s, over 70% of the annual output of German films was exported – a record for the ages. In addition to all the other factors, the cinema of the Weimar Republic had one main advantage for exports that was soon to disappear: it was silent film and therefore a cinema without a language barrier.

Wolfgang Staudte 1955 © Noske, J.D. Anefo - Nationaal Archief

But back to the 1950s, when the export of West German films faced completely different challenges. There were numerous reasons for the export weakness after the end of World War II – for example, the fact that all structures first had to be rebuilt in a rather lengthy process: film had been misused by the Nazi regime for propaganda purposes to such an extent that the Allies initially stopped all film activities completely in 1945 with the aim of smashing the fascist propaganda monopoly and comprehensively reorganising the industry’s structures. All administrations in the four occupation zones initially pursued their own plans for rebuilding the film industry. It was not until October 15, 1946 that Wolfgang Staudte’s THE MURDERERS ARE AMONG US premiered, the first German feature film to be produced after the end of the war, namely by DEFA under a Soviet licence. Nine more films from the four zones followed in the course of 1947, and another 22 in 1948.

In the first two post-war years, however, film exports were out of the question, not only because of the lack of films, but also because all German trade was initially cut off by the Allies anyway. In addition, the distribution of newly produced films within the four zones was difficult enough because there was no distributor allowed to operate in all four zones. So in June 1947, a complex four-power agreement was reached on the exchange of films between the occupation zones, in which all the occupying powers were able to make their selection according to their own criteria. The DEFA film MARRIAGE IN THE SHADOWS (1947) by Kurt Maetzig, for example, was one of the few films to be released simultaneously in all four zones because all of them apparently appreciated its “great educational value”. Only in October 1948 was it possible to establish free film distribution within at least three zones, the American, British and French ones – the “film border” with the Soviet zone remained in place, however.

Omnia Deutsche Film-Export-Logo

From 1948, foreign trade in the western zones was initially handled by the Joint Export Import Agency (JEIA), which treated goods such as cuckoo clocks in the same way as feature films. There was a lack of specialised knowledge as well as capacity: The issuing of import and export licences is said to have taken up to nine months.

In the Soviet zone, where the film sector was basically structured on a centralised basis by DEFA, things were handled much more professionally from the outset: The film trade was initially taken over by Sovexportfilm, which specialised in it, before the VEB DEFA Außenhandel was founded in two stages up to 1955, which handled the GDR’s film trade until 1990. DEFA exports were thus organised in a stable manner early on.

This was not the case in the western zones and, from 1949, in the newly founded FRG. By September 1949, only eight of the 50 or so films produced to date had been sold abroad. Only a few distribution companies had a foreign department, such as Herzog-Filmverleih, which succeeded in selling its operetta title MASK IN BLUE (Georg Jacoby, 1952) to almost 40 countries. But such successes were rare. Individual world sales companies such as the later very successful Exportfilm Bischoff or Omnia Deutsche Film-Export only began their work around 1950.

Cover Magazin Filmblätter1955

It was therefore time for a specialised contact point to create a better environment for the export of West German films. In 1954, this gap in the structural fabric of West German film was closed with the establishment of the Export-Union – seven years after the first West German film was completed. Two years after the Export-Union began its work, the film trade magazine “Filmblätter” was quick to offer compliments: rising revenues in 1955 and 1956 were “primarily due to the work of the skilfully operating Export-Union”. From 1954, foreign film revenues doubled to DM 25 million by 1958.

The complicated rebuilding of structures in the domestic film industry as an obstacle to film exports was accompanied by the general economic and political rebuilding of foreign connections and film-specific distribution channels. These in turn were closely linked to the understandable resentment against Germany just a few years after a Nazi dictatorship that was responsible for the deaths of millions of people. The inhabitants of the countries formerly occupied by Germany, whose cinemas were flooded with UFA productions during the occupation, had lost their appetite for German cinema.

Especially as German post-war film was still strongly characterised on many levels by an enduring UFA continuity. Former UFA functionaries in important film policy positions was one thing. However, the fact that the majority of filmmakers had learnt or practised their craft at the UFA and – at least in West Germany – saw little reason to change the tried and tested narrative style was a decisive factor in the difficult export situation. They maintained the continuity on the one hand, because the familiar style represented a security in the way they worked under otherwise difficult conditions. But also because the German audience was used to this UFA style and probably liked it very much. This can be seen quite clearly in the popularity of the so-called “Reprisen” (re-runs), i.e. entertaining UFA films from the Nazi era that were released by the Allies as unobjectionable and were shown in cinemas until the early 1960s (and later also repeated on television). Even between 1955 and 1958, these re-runs still generated a turnover of over DM 5 million at the cinema box office. Remakes of UFA films were also very popular: 95 UFA films that had already been filmed between 1933 and 1945 were remade and brought to the cinema between 1949 and 1959.

After all, this UFA style proved to be successful. The restructured film industry in the 1950s seemed to be content with exploitation on the German market with cinema revenues of DM 154 million for German films alone (1956). An average film had to sell around three million tickets in those years in order to pay for itself – and this could easily be achieved on the German market with the tailor-made Heimat and revue films in the UFA style alone.

Apart from the brief phase between 1946 and 1949, when the two German states had not yet been founded and rare “rubble film” gems could be made, West German film had not been able to develop a new wave à la neo-realism that could have been attractive on the international market. Its international successes were limited to individual films and directors, from Wolfgang Staudte to Helmut Käutner and Kurt Hoffmann, who were celebrated – thanks to the Export-Union – at film festivals around the world. The DEFA films of those early years, on the other hand, often surpassed the majority of their West German counterparts. However, they were rejected by the West as being too ideological, but celebrated regular successes in countries of the political East.

Oliver Baumgarten