A PORTRAIT OF DIRECTOR ROBERT SCHWENTKE

Robert Schwentke (© Jennifer Howard)“Many films that handle the issue of violence offer a loophole. I don’t want to leave the audience any loophole.” As a person, Robert Schwentke has a striking sense of humor, but the film director in him takes this absolutely seriously. “I don’t think it’s funny when people get their heads shot off," Schwentke says, referring to his latest film, THE CAPTAIN.

What triggered this attitude for him was probably Stanley Kubrick’s A CLOCKWORK ORANGE. “Kubrick’s anger was not understood by audiences. At that point, I realized that as a director you have to deal with violence very cautiously.” The other way around, he has no faith at all in the moralist position, either. “The cinema is not a place to preach” or for puritanism. “It would be dishonest not to show violence at all.”

In Germany people are not really aware of the fact that Robert Schwenkte is one of the most important German filmmakers already, since he has achieved what many can only dream of: he makes major commercial studio films in Hollywood with stars like Bruce Willis, Kate Winslet or Jodie Foster, and yet he is also able to realize a personal project like THE CAPTAIN now and then.

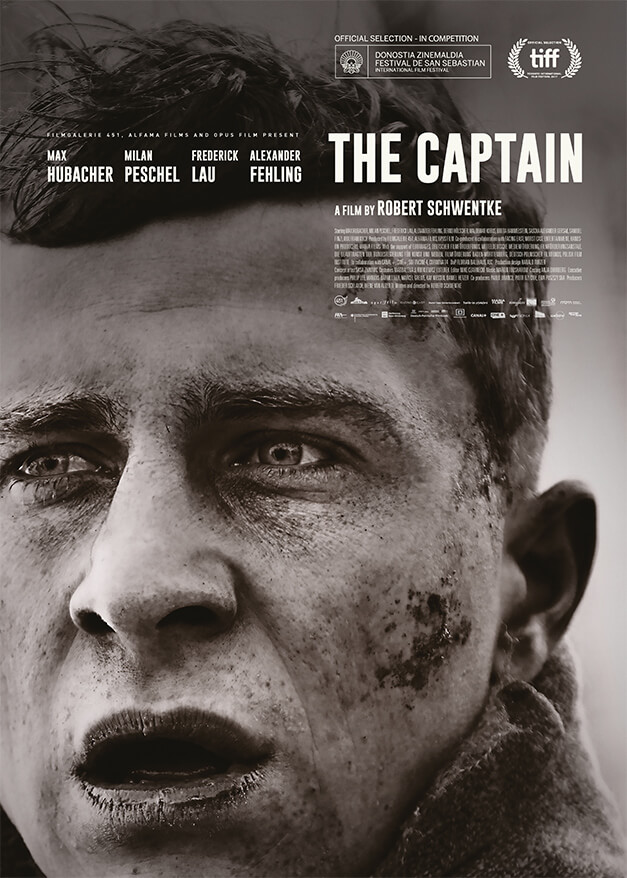

In this sensational film Schwentke took a look at National Socialism in an unprecedented way, at least in German cinemas: he made a film that shows National Socialism as the bloody travesty, the imposture, and the outpouring of suppressed bestial drives that it was – at last, a film from Germany that depicts German fascism from its most repugnant aspect, without Nazis who somehow have ‘good reasons’ for their actions.

Schwentke’s convincing debut as a director was with TATTOO in 2002: a dark, powerfully visual serial killer thriller in the tradition of David Fincher’s black romanticism. Schwentke did not ask himself what would be permitted in a German film, he simply made it: a film without true villains, but definitely without a true hero, either – cinema of irritation. All in all, TATTOO was unquestionably an event – which, however, in the period between the comedy boom, “Berlin-Film”, and the early “Berlin School”, disturbed the German film scene rather than leaving it suitably fascinated.

Schwentke had always done his own thing. In 1989, when the youth of West Germany were travelling to Berlin to get intoxicated over the fall of the Wall, Stuttgart-born Schwentke abandoned his studies of Philosophy and moved in the opposite direction: he applied to the acclaimed Los Angeles Film School with a black and white, 16 mm experimental film, where he was accepted and studied together with the likes of Darren Aronofsky and Todd Field. After five years he returned to Germany. Initial projects failed as a result of the bureaucracy of the film business. Then he became seriously ill with cancer. Schwentke’s second feature film, THE FAMILY JEWELS (2003), was a cinematic version of this phase in his life – a testicular cancer comedy and a life-affirming film about death, which brought the director several offers from Hollywood. Since then, he has also had a home in Los Angeles and “commutes” between the two continents.

The first outcome of the move to America was FLIGHTPLAN (2005), a “post-9/11” paranoia thriller starring Jodie Foster about a group in a state of claustrophobic fear, set in an airplane transformed into a panic room. Then, in 2009, there was THE TIME-TRAVELLER’S WIFE – a highly poetic, quiet, science-fiction love story. This work also confirms Schwentke’s love of romanticism. In his next films, however, he has been able to live out various other sides of his personality as well as his professionalism.

“I admire people like Soderbergh. They make a studio film, and then they make something much smaller.” He worked on the material for THE CAPTAIN for almost 20 years. “I needed that time in order to gradually draw closer to the subject.” This director talks repeatedly about journeys of initiation: a young, blank page encounters an extremely cold, disintegrating world. On the journey he discovers himself and becomes a different person.

We are likely to find all this again in Schwentke’s new projects: he is currently writing an adaptation of the post-apocalyptic novel Ship Breaker, gathering material about the polio crisis in the 50s, and – together with his producer Frieder Schlaich – he is planning a film about the stoic philosopher Seneca and his pupil, Emperor Nero.

Rüdiger Suchsland